13 Oct 2023

Every 2nd Friday of the month, my dive shop hosts a Coral Restoration dive that I’ve wanted to do for ages, but the timing never works out with my time off. When I first started planning this trip and noticed this Friday was a coral Friday, that cinched it for me.

My morning started at the Coral Restoration Foundation, where we learned about coral, the role they play in the reef ecosystem, and the threat they are facing. I’ve been diving in the Keys for about 8 years now and each time I come back, it feels like there’s less color, less life, and it’s not just the Keys- it’s estimated that over half the coral reefs worldwide have died in the last 30 years.

I’ve heard how the Great Barrier Reef is struggling and I’ve seen firsthand how the coral here is bleached and struggling…

Reefs act as a barrier between ocean and shore, protecting shores and mangroves from waves that would damages coastlines. They support marine life, providing a home for fish and marine life with protection, and when fish populations are healthy, fishing industries can thrive. Healthy reefs attract divers and tourists, which support local economies. So many ecosystems depend on the reef, but rising ocean temperatures and other stressors (pollution, harvesting of coral, disease, chemical sunscreens) are threatening coral.

The Coral Restoration Foundation is working to restore and regrow reefs here in the Keys. They have extensive off-shore nurseries where corals are grown on trees like this:

The nurseries are shallow to allow plenty of sunlight to reach each coral fragment, and the tree structure lets nutrient-rich waters to flow around each piece. Fragments spend about 6-9 months on the tree until they are big enough to be outplanted back to the reef.

We practiced “planting” corals here:

Each site is tagged to allow progress to be tracked, and corals are planted in groups by species and genotype. They’ve noticed that some genotypes tend to do better with temperature changes, some are more resilient to disease, but they don’t discriminate and plant as many different genotypes as possible, some of which are no longer found in the wild (except where they have been planted). Corals of the same genotype will merge and form thickets, which are stronger structures than individual corals.

While initially they fragmented corals from existing reefs along the coast (which is one of the ways corals are propagated), they are now entirely self-sustaining and have one of the largest coral “banks” in the world. Corals that have been outplanted have begun spawning naturally!

This is a site called Carysfort Reef- the picture on the left is from 2017, about 8 months after the corals were outplanted; the picture on the right is from 2 years later:

Photo from Coral Restoration Foundation / www.coralrestoration.org

But there’s currently a hold on outplanting due to the high water temperatures- any new corals placed out on the reef will likely die, or seriously struggle, so our plan for today will be to clean the coral trees. Algae and other invasive organisms also grow well on trees, so we’ll be removing them to minimize competition to the growing corals.

Or, at least that was the plan… while we were practicing our techniques, we got a call saying there’s still a bit too much surge for us to go out. The nursery is shallow so we’d be tossed around while trying to clean, and no one wants to inadvertently damage the coral. No coral dives this afternoon. Ugh. Bad luck strikes again.

But the regular dive boats were still going out, so I called the shop and, while all the boats were full, they said they’d find a spot somewhere for me. My boat changed a couple times, but I eventually landed on a student boat, with a crew I knew and had dived with previously!

First mate on my boat was Elliott, who has a fun sense of humor and is full of corny jokes; Jack, who was teaching a photography class, but still took the time to point out blennies to me; and Chris, my guide, who stopped frequently to allow me to catch up (I get distracted easily by fishes and other critters begging to be photographed) but also didn’t worry if I lagged too far behind because he knew I would always catch back up.

Dive #5 – Spanish Anchor

Unfortunately, I’m still struggling with lighting. I thought I was getting close enough to my subject, but it feels like my strobes just aren’t putting out as much light as I think they should be. Not sure how I troubleshoot that, but here’s an incredibly poorly lit (and incredibly derpy) hogfish:

Harlequin bass:

Midnight parrotfish:

Foureye butterflyfish:

GOLIATH GROUPER!!!

All the sites here on Molasses are fairly close together and we swam our way over to the ledge where the Goliath groupers like to hang.

They’re big and hard to light, but I’m glad I got a second shot at getting a picture of them!

Trumpetfish:

Blenny!

Look at his little eyebrows!!!

Dive #6 – Hole in the Wall

Lettuce sea slug:

Another diver pointed this guy out to me- we don’t see a lot of squid here in the Keys. This guy was initially perched photogenically atop a reef, but by the time I got close enough for a picture, he took off, so this is the best I could do:

Blenny:

Juvenile Spotted trunkfish!!!

This little guy was hiding in a cave and would only peek out occasionally.

OO, barracuda!

Green Moray eel:

Spotted drum (adult):

(not a great picture, but I don’t see these guys very often)

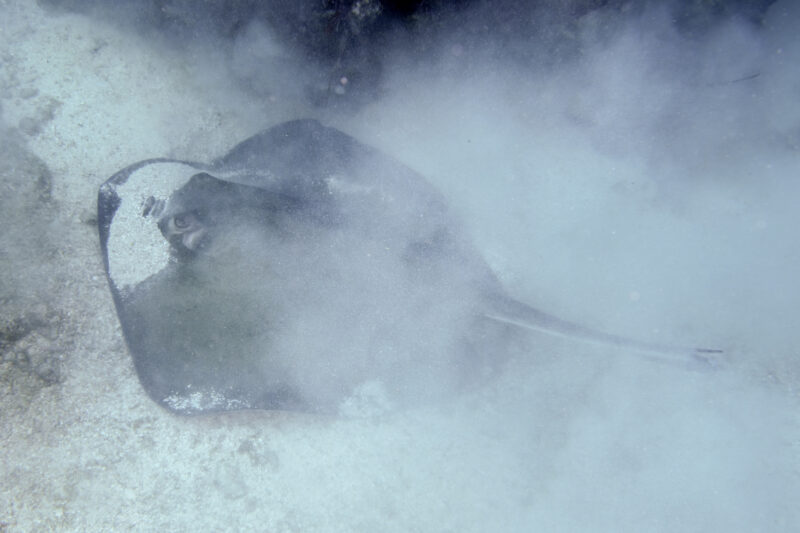

Ray, trying to bury himself:

Little hermit crab:

Yellowtail damselfish:

I’m not sure if this is half a lettuce sea slug, or 2 smaller ones making more sea slugs, but I really hope it’s not one guy who got chomped in half:

Ok, this picture is blurry because it was super-surge-y at the surface, but there were TONS of these Moon jellies hanging around the boat:

You can kind of see a rope behind the jelly off to the left- our boat throws out a tagline off the back of the boat for us to hold onto while we take off our fins and to keep us from having to fight the surge. Usually I wait until there aren’t any divers left on the line (or the last person is getting ready to climb the ladder) before I join the line so I’m not bobbing around the surface, but there were a lot of jellies and the line was clear, so I decided to surface first. I was pulling myself to the boat when another diver surfaced into me. Poor form. He never even looked back and then took FOREVER getting his fins off. Ugh.

So, as I bobbed around waiting for him to get his act together, a wave crashed over me and washed a jelly into my face. HOLY COW DO JELLY STINGS BURN!!!

I was wearing a hood, which, along with my mask and regulator, protected most of my face, but my chin and neck were exposed (I didn’t have my hood tucked into my suit) and took most of the hit.

I tried to wash it off as best I could while I was still in the water, and Elliott had a spray bottle of vinegar (which neutralizes the nematocysts, or stinging cells), but I definitely had jelly parts on me and anyone who touched me as I got onto the boat got stung (sorry, crew!!!).

The look of someone who just got hit in the face with a jellyfish:

It was a solid 45 minutes before the stinging had mostly subsided, though there’s a spot on my chin that still tingles a bit even a few days later.

Fortunately, Moon jellies are some of the “nicer” jellies- their sting isn’t as bad as some, so while it was definitely uncomfortable, I didn’t have too terrible of a reaction. It feels almost like a rite of passage 🙂

I’m so glad I was able to dive today, and that I got to dive with people I know. I was feeling pretty down about this whole trip, but this afternoon put me in a much better mood.